Smithereen Stories: From Fossils to Floppy Disks

Kira Westby and the newly-painted Central Park Building. Photo: @malcolmrjohnson

If you’d like to learn about the long, fascinating, and sometimes surprising history of the Smithers area, one of the town’s most historic buildings is probably the best place to start.

Set in the century-old Central Park Building at the corner of Main Street and Highway 16, the Bulkley Valley Museum is dedicated to preserving the heritage and culture of the town and its surroundings, from the time of the fossils to the bygone age of film canisters and floppy disks—which, for kids these days, is pretty much ancient history.

Sharing the main floor with the Smithers Art Gallery, the museum’s staff and volunteers have spent decades amassing a diverse collection that includes 3600 artifacts, 7000 photographs, and thousands of maps, documents, and archival records. Now overseen by curator Kira Westby, the museum’s permanent and seasonal exhibits hold plenty of fascination for all ages and interests—in less than half an hour, you can learn about Scandinavian kicksleds and Wet’suwet’en cottonwood canoes, admire old-time typewriters and intricate baskets, and browse through railway menus from the days when a full supper would only set you back 70 cents. If you’ve got young ones with you, they’ll likely race around with the museum’s scavenger hunt sheets, or set themselves up behind the twin machine guns of the atomic-armed B-36 bomber that crashed in the mountains in 1950.

Though all the museum’s exhibits are interesting in their own right, the tale they tell together is even more so—a continuing story of diverse peoples making their homes, through many changes and challenges, in this beautiful valley carved by the glaciers so long ago.

Open six days a week with admission by donation, the museum is one of our favourite places in town. So on a sunny summer’s day, we sat down with Kira to chat about the museum’s collections, what brought her to Smithers, and what she’d like to take home if she could. And, of course, we talked through the origin story of the egg carton—the Bulkley Valley’s most famous gift to the modern world.

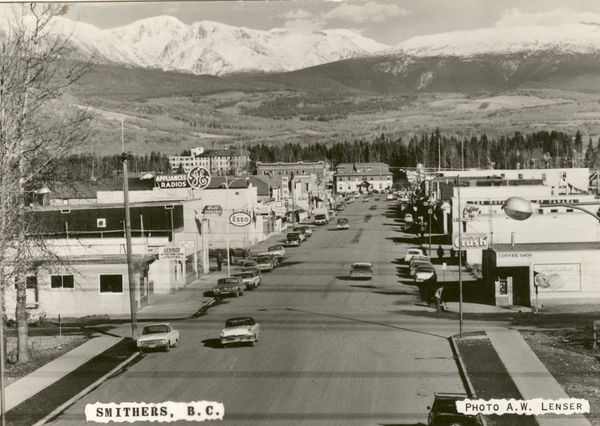

Main Street in the late 1950s. Photo: Bulkley Valley Museum

How did you become the curator of the Bulkley Valley Museum?

I’m originally from Ontario, where my education was in history and archaeology. I was working in London at an archaeological facility, but it was short-term, and I was applying for jobs elsewhere. One of them was this role here in Smithers, and I actually had to look it up on the map to see where it was. I had an interview, was offered the position, and my partner and I packed up everything in a U-Haul and moved here sight unseen. But we’ve really grown to love it, and we’ve been joking that we’re now on year six of our five-year-plan.

Locals outside Sargent’s Store in Smithers, ca. 1920s. Photo: Bulkley Valley Museum

It must have been interesting getting to know the town through its history.

Yes, for sure. Coming from Ontario, I’m used to a longer settler history than there is in Smithers. The Indigenous history is obviously much deeper in both places, but when I first got here I thought, “Oh, the town’s only 100 years old, it’s going to be mostly modern history.” But there are a lot of interesting things that have happened in connection to broader trends. There’s the railway, mining, and forest history—and the fact that the Delgamuukw trial started here, in terms of Indigenous rights movements, is really fascinating too. And despite only living here six years, I probably know more about how the town has grown and changed than many residents do. When we first arrived I made a lot of friends in the community who were older, so hearing them talk about the community and how it’s evolved over time was a really neat education.

Is most of the collection on display, or are you constantly changing what’s available to view?

Well, one thing they say about museums is that only between one and three percent of the collection is ever on display. And because our space is small, that’s definitely true for us. We have certain themes, like the railway history and the introduction to the history and culture of the Wet’suwet’en, that are permanent. Then we have temporary exhibits rotating through—our current one is just weird and wonderful artifacts we haven’t displayed before. I should mention that our egg carton exhibit is permanent too—we have so many in the collection, and we seem to get given egg paraphernalia all the time.

So is it true that the egg carton was invented here in Smithers?

Not exactly—it was in Aldermere, which was just down the road from here. Joseph Coyle was the inventor, and apparently it came from overhearing an argument between a hotelier and a farmer because the day’s eggs were all broken again. Coyle had started a paper called the Bulkley Pioneer, which when he came to Smithers became the Interior News, still our local paper and now over 100 years old. Along with the paper he produced things like stationery and butter wrap—anything that could be printed—so he came up with the egg carton idea and started making them. Then after that he left down, moved to Los Angeles, and set up a factory there. So yes, the egg carton is from the Bulkley Valley.

But then he went Hollywood.

Exactly.

A downtown dance party in 1963. Photo: Bulkley Valley Museum

Other than the cartons, what do you think are some of the most interesting artifacts people can see when they visit?

I like the objects that have a true story that goes with them, and that covers almost everything in the collection. Personally, I really like the clothing—you see the little tears or the buttons that were replaced, things that were part of the lived history. We had a wedding dress on display not long ago, and I’d printed out a bunch of photos from the collection of people in cool outfits, and I realized one of them was wearing that same dress. That’s a neat feeling when you’re putting something on a mannequin and the last time anyone wore it was over a century ago. Another neat piece we have is a dumpy level for surveying and building, which was used by the Bovill and Hann Company to construct many of the buildings in town. I also really love glass bottles, and we’ve got some neat old medicine ones where it’s like, “Cures everything from your head to your toe, your skin ailments and your stomach problems, and it’s good for your dog too.”

Fun times at the 1977 Fall Fair. Photo: Interior News / Bulkley Valley Museum

How about for kids? What are some of the things they tend to find most interesting?

They like the old toys we have on display at the moment, and a lot of them gravitate to the gun from the B-36. But it’s also interesting that some things are totally lost on them—we did a display of cameras one year, and we had rolls of film on our scavenger hunt. But they had no idea to look where the cameras were for these rolls of film, because they’d just never seen them before. Same with the floppy disks that are on display with the computer. And things like the butter churn—our grandparents may have used tools like that, but for kids now, those technologies are getting farther away.

How about the objects that come from the area’s Indigenous history?

Oh, they’re amazing. I really love the baskets—the skill to make them is just so incredible. And the fish trap we have is really interesting as well. We have some projectile points in the collection, and those are neat to talk to kids about too—we explain to them the huge amount of knowledge that was required to know where on the territory to find different types of stone and how to work it into usable tools. Stone tools seem simple at first, but making them was actually so complex. It’s great to be able to teach about the knowledge that Indigenous people had, and continue to have, of their territory, and how that’s present in the material culture. But more than anything I like to refer people to go to the museum in Witset—they can teach so much more about their culture than I can, and to learn about those connections and history is pretty incredible.

Would those projectile points be the oldest items you have?

The oldest human made ones. But the oldest are the fossils. We’ve got the Driftwood Canyon fossils, like Eosalmo driftwoodensis, the oldest species of salmon. We don’t know the exact age of the projectile points, because they’re what we call surface finds, and you can only date stone tools when they’re found in layers of stratigraphy. We also have a rib bone from the Babine Lake mammoth in the collection, and that was recently sent to Simon Fraser University for radiocarbon dating,

As a last question, if you could take home one thing from the collection, what would it be? Or maybe you’ve done that already? I think I’d take the cottonwood canoe.

Ha! No, I haven’t—and that canoe actually has a pretty big hole in it. I think I’d take home Joseph Coyle’s typewriter. I like to imagine him sitting there writing Interior News editorials back in the day. It’s a nice old executive one, so I think that would be a neat thing to have in the house, especially if I could get a ribbon for it and get it working again.

For more about the museum’s exhibits and collections, including its virtual ones, visit its website here. You can also follow the museum on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Connect with us